Transfinite Zippers

In my previous post, I described an approach for extending multi-stage programming (MSP) to infinity and beyond. We start with a simple computing “machine” M[0] such as the lambda calculus. Each machine M[a] has a successor machine M[a+1] which is capable of building and reasoning about programs from M[a], yielding towers of nested machines. From there, we note that MSP itself can’t be implemented in any such finite M[n], but must exist in some limit machine M[ω], yielding transfinite towers of machines M[a] for each ordinal a.

In another post, I defined a data structure used by such transfinite machines to encode mappings of variable indices to bound values. This post describes a new and improved data structure for these mappings.

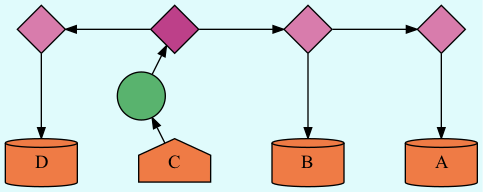

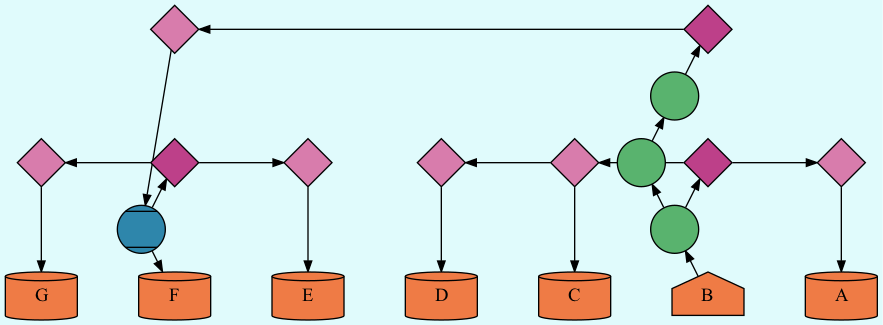

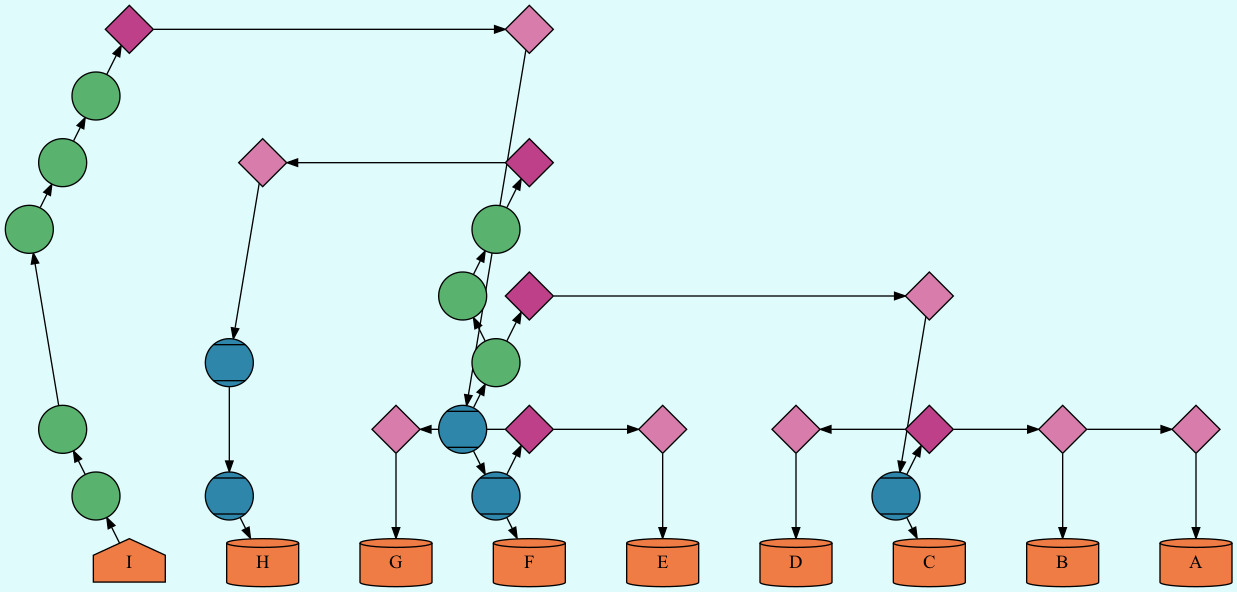

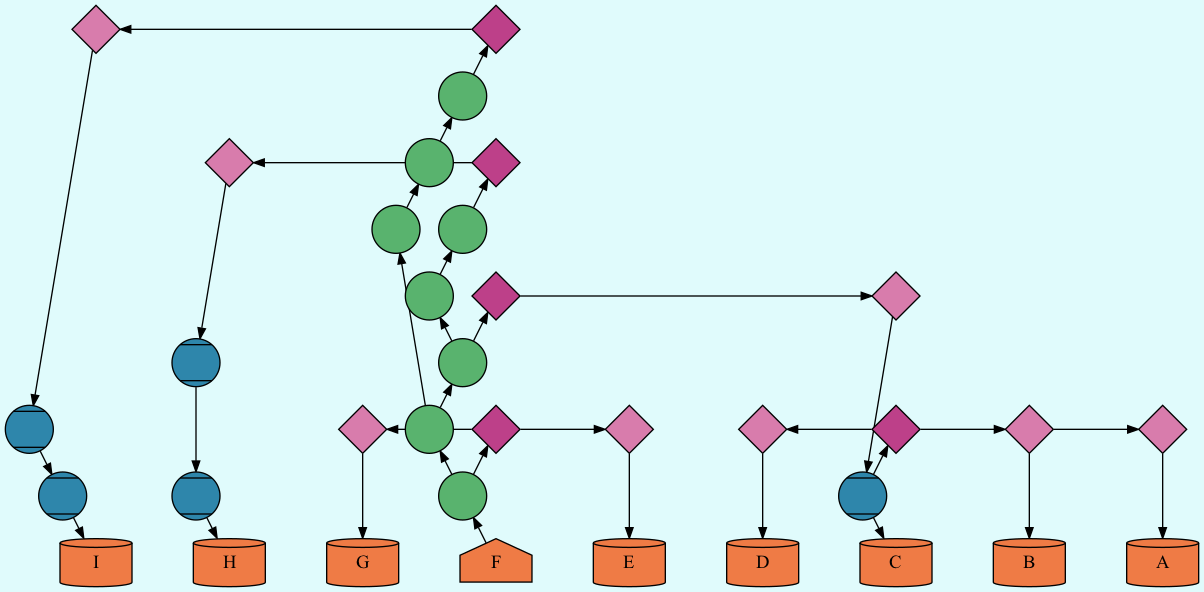

During the evaluation of a program in which a function was passed the values A, B, C, D, in that order, we might see a mapping like:

The orange house holds the most recently bound value, in this case D, which can be immediately retrieved. The orange buckets hold other values we can access at offsets {1:C, 2: B, 3: A}. The pink diamonds build the intermediate list structure, and the green circles can be ignored for now. We effectively have a simple linked list. From here, we might do a move(1) to get to the mapping:

The house now points to the value C for retrieval. Note how we have retained access to D by pointing to the left. We effectively have a pair of linked lists, sometimes called a zipper list. Another move(1) gets us to:

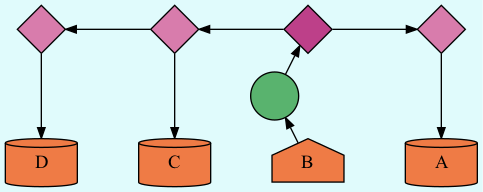

This encodes a function from index differences to values {-2: D, -1: C, 0: B, 1: A}. Now it’s time to jump to a new machine with a move(ω), followed by a set(E) to help keep track of where we are:

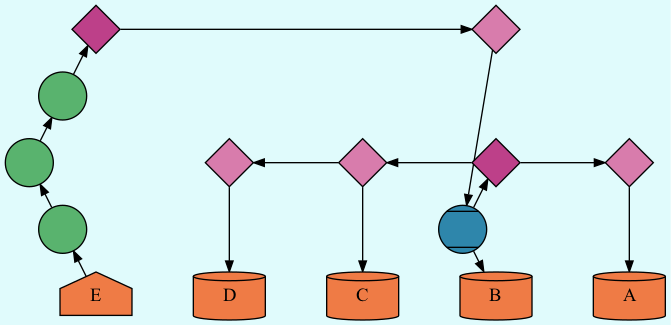

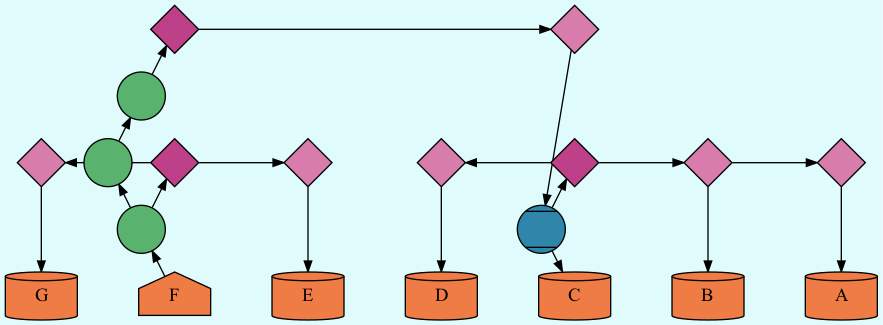

This movement is what happens when the interpreter begins processing a [`ω] quote. The values A, B, C, D live in the successor machine to that of E. Note that that value E is stored at a new place beyond the reach of any number of move(1)s. I’ll explain the meaning of the green and blue circles soon, but to make it clearer that we’re starting to build up a tree structure, lets do some move(+/-1)s in the new machine:

We can now see some hierarchical structure to the values. If we think of this as part of a family tree focusing on F, values G and E are its 0th cousins, also known as siblings, and values A-D are its 1st cousins. This data structure stores the additional information of a “chosen child” for each “uncle”. For example, B is chosen, because that was the value in focus when we last left that machine. Now lets move back to that machine with a move(ω):

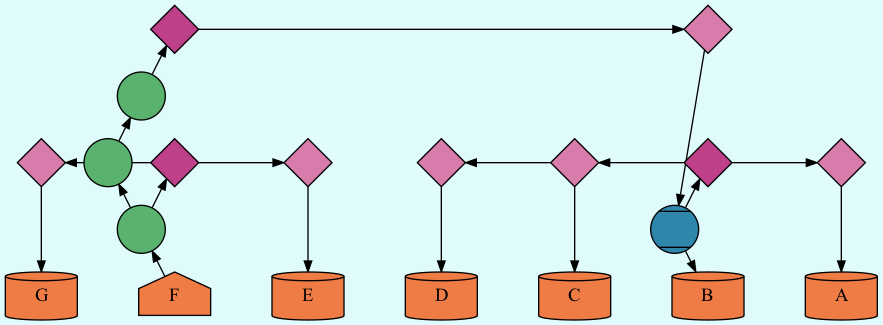

We’re now once again focused on B, and the F where we were is left chosen by its parent. We effectively have a rose tree with zipper lists of children. This movement corresponds to a [,ω] unquote. Now we might do some local processing with a move(-1) followed by quoting with another move(-ω):

Unsuprisingly, we find ourselves at F again, but this is a crucial improvement over transfinite lists which would have forgotten the local context/values/siblings in this machine. I won’t try to justify it here, but this retentive behavior is what is needed enable programs to not just build, but reason about programs without losing information about bound variables.

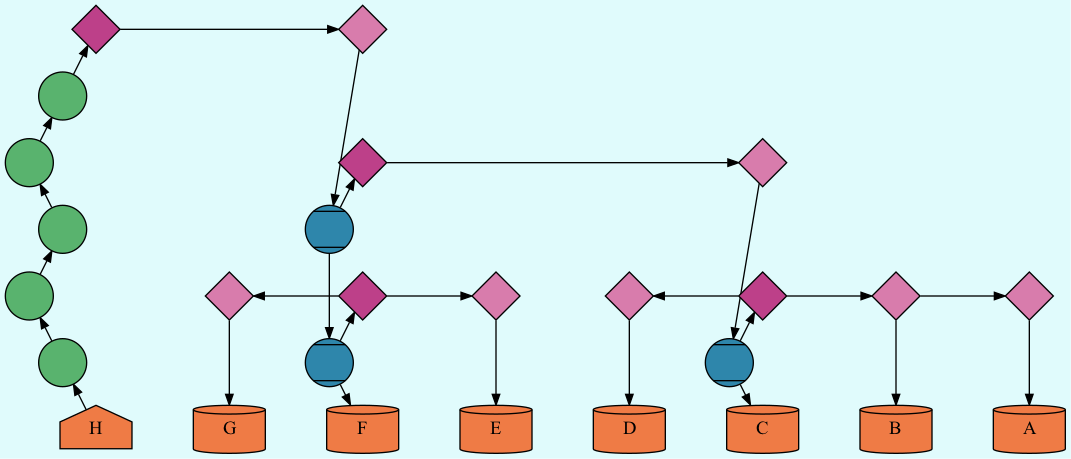

Now we move beyond MSP by jumping to an entirely different infinite tower of machines with a move(-ω²) corresponding to a [`ω²] “big” quote:

Actually, this is lonely and weird, so lets move(ω²) back:

Okay, that’s a little more familiar, so it’s time to talk about the green and blue circles. From where we stand at F, we see a winding vine of green circles taking us upwards to our ancestors in the tree. This vine is actually a trie of left and right movements, and these movements correspond to left and right parens in the bounded parentheses notation for ordinals that I wrote about here. As I did there, I’ll replace left and right parentheses with and / respectively. Note that this ordinal notation only gets us up to ε₀ but the technique described here can be extended to higher ordinal notations fitting certain criteria.

In figures 1–3, we were moving by integer multiples of 1, which is represented by \/. This tells us to move up the trie following first a and then a / edge to reach a dark pink diamond, move along the zipper by the integer multiple to a light pink diamond, and then follow the reversed path downwards, rebuilding the vine in the new location.

In figures 4–7, we were moving between machines by integer multiple of ω, which is represented by \//, and so we follow that path up and down to get to 1st cousins. In figures 8–9, we moved by integer multiples of ω², which is represented by \/\//, which is the longest path we see above us from F, and takes us to its 2nd cousin H.

The blue circles with the horizontal lines enable this by keeping around the unfocused structure. They are created when following a path upwards whenever we move left and store the right path we leave behind. They are used when following a left path downwards and get reattached to the right of a green trie node.

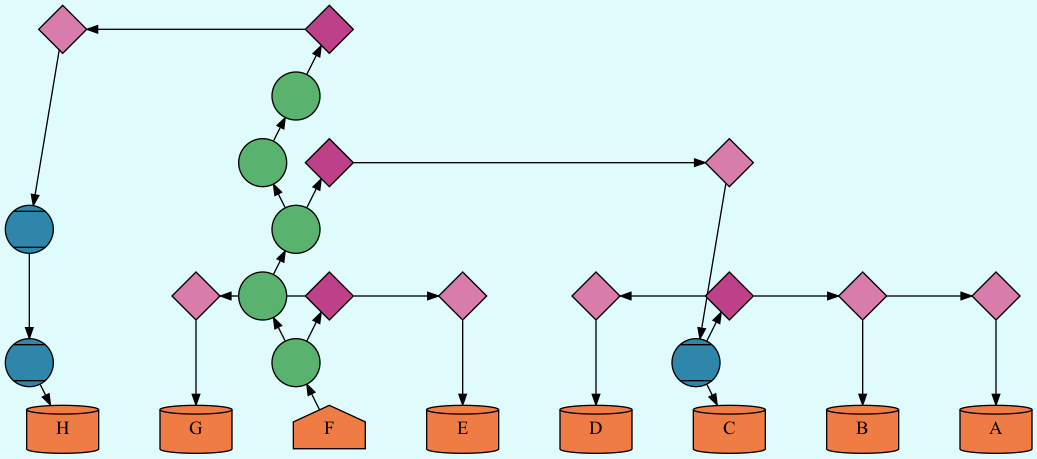

Instead of trying to explain why this works, I’ll let the diagrams speak for themselves. Let’s finish with a move(-ω^ω):

And a move(ω^ω) back:

Note that we still have two important properties that the transfinite lists had. First, the data structures are pure and immutable which is needed for use in recursively defined interpreters. Second, the amount of work done for each movement is proportional to the size of the representation of the ordinal, and is independent of the size of the whole data structure. It may look like lots of changes are happening from figure 10 to 11, but observe that the structures pointed to by blue circles in figure 10 are entirely untouched in figure 11.

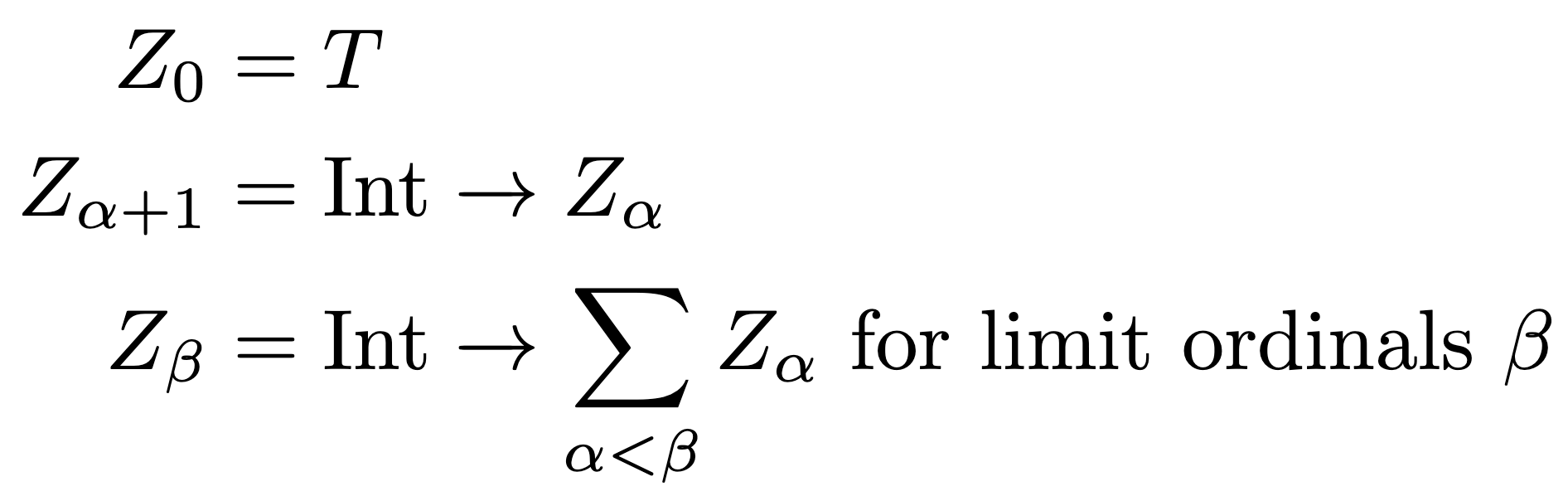

We effectively end up with zipper versions of the type family:

I’ll end by returning to the family tree analogy. If a move(ω^n) takes us to our nth cousins through n generations of ancestors, a move(ω^ω) takes us through individuals ancestral to yet distinct from all of our ancestors. These individuals can have siblings and relatives of their own. I’m told certain belief systems have names for such individuals.

Thanks to my wife Mary Kate Bell for consulting on the diagram vibes, and to Stefano Gentili for helping me understand what on earth I was defining in the first place.